The Tragedy of Macbeth, Joel Coen’s first filmmaking venture apart from brother Ethan, owes something to Akira Kurosawa and something to Alfred Hitchcock. Of the many cinematic versions of Shakespeare’s famous tale. Kurosawa’s 1957 Throne of Blood seems the closest match to what Coen has accomplished. The Japanese-language Throne of Blood, freed of the need to grapple with Shakespeare’s challenging but beautiful language, is marked by spare, spooky stylistics. Shot in black & white, it fills the screen with bleak, ominous visuals. The scene of a fog-shrouded “Birnam Wood” slowly creeping toward the new lord’s Spider’s Web Castle is as spectacular as it gets. Calling on Kabuki tradition, Kurosawa alters the familiar tragedy to enhance the bombastic acting style of the classical Japanese stage. But it’s the look of his film that has stayed with me, and clearly with Joel Coen too. (The American Society of Cinematographers has just named this Macbeth one of 5 nominees for this year’s ASC award, along with Dune, Nightmare Alley, Belfast, and The Power of the Dog.)

As for the Hitchcock influence, let’s simply say that in The Tragedy of Macbeth there will be birds.

Visually, Coen strips his Macbeth down to the bare bones: even the unusual aspect-ratio makes for a movie screen—almost square—that hints at long ago and far away. Realism is hardly the point here. Props and set décor are kept to a minimum. Color is bleached out: this is one of several important 2021 films that stick (as Kurosawa did) to stark black & white. Characters wander through nearly empty halls photographed from often-exotic angles.

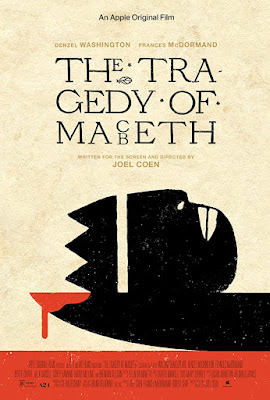

And what about those characters? Commendably, Coen has chosen to be color-blind in his casting, peopling his landscape with actors of different races. The fact that a Black Macbeth (Denzel Washington) is closely allied with a white Lady Macbeth (Coen’s wife Frances McDormand) is never held up for comment. Though the screen is shared by British and American actors, no attempt is made to unify their speech patterns. For this I have some slight misgivings. Though I’ve never been a fan of old Hollywood’s “mid-Atlantic” accent that makes everyone seem vaguely British (see Price, Vincent), I appreciate the vocal precision that the English actors in this cast bring to their roles. McDormand (who can do no wrong in my book) does a magnificent job of articulating her lines while not departing from basic American speech. Alas, I had a harder time with Washington, who sometimes seemed less comfortable in “speaking the speech” while pulling away from the naturalism he brings to present-day American-based stories.

I wanted to love Washington’s performance, as many critics have. But in the play’s key early moments, I couldn’t quite feel the tug-of-war going on in him between Macbeth’s ambition and his fundamental civility. It was only in the later scenes, wherein the newly crowned king lashes out at anyone who stands in the way, that I felt the full force of his portrayal. McDormand, though, is from the start a forceful Lady McDormand, in love with her husband and his potential for greatness, however he achieves it. There are many fine supporting players, including Brendan Gleeson as King Duncan, Corey Hawkins as a well-spoken Macduff, and Alex Hassell as an enigmatic Ross (whose role is given an extra twist by Coen).

But many kudos have rightly gone to British stage actress Kathryn Hunter, who uses her voice and a highly flexible body to channel all three of the Weird Sisters who accost Macbeth on that heath. Hers is an otherworldly performance just right for this somber, exhilarating tale.