After The Godfather (1972) and The Godfather, Part II (1974) swept up every honor in sight, Hollywood couldn’t get enough of Italian-American mafioso types. But well before Martin Scorsese’s Goodfellas (1990, starring the late Ray Liotta) and TV’s The Sopranos (for six seasons, starting in 1999), came Prizzi’s Honor, directed by one of Hollywood’s oldest and feistiest lions. I’m talking about John Huston, responsible over the decades for such studio gems as The Maltese Falcon in 1941, The Treasure of the Sierra Madre in 1948, The African Queen in 1951, and The Man Who Would be King in 1975. As an actor, he also turned in an unforgettable performance as sinister tycoon Noah Cross in 1974’s Chinatown. Prizzi’s Honor was released in 1985, when Huston was almost eighty. It was his last film but one; he followed it up with a poignant adaption of a James Joyce story, The Dead, made as he approached his own death in 1987.

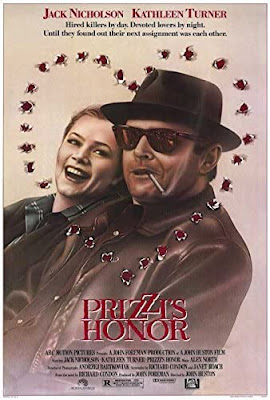

Prizzi’s Honor, too, has its somber moments, but it is at base a comedy, if an extremely macabre one. Jack Nicholson, reuniting with Huston a decade after Chinatown, plays a Mafia hitman with a deep loyalty toward his ancient padrone. The latter, Don Corrado Prinzi, is vividly played by a sepulchral-looking, gravel-voiced William Hickey, who earned an Oscar nomination for this role. The body of the film starts, à la The Godfather, with an elaborate cathedral wedding scene in which an overblown bride is joined in holy wedlock to a shrimpy little groom, as a massive group of wiseguys looks on with approval. Nicholson’s Charley Partanna is one of them, cocky and slightly cynical about the world around him, but newly entranced by the unknown blonde in the balcony.

That luscious lady in lavender is played by Kathleen Turner, just three years after she’d burst onto the screen as the dangerous Matty Walker in Body Heat. Svelte and blessed with an seductively throaty voice, she couldn’t be more enticing. Of course Charley is smitten, but the surprise is that she seems to be enraptured by him as well. Their coupling plays out both in New York and L.A. (lots of amusing shots of a now-defunct airline heading right to left, then left to right, across the screen). But who is this mysterious blonde, and what’s her game? The audience figures it out before Charley does. (He’s not too smart. She likes that in a man.)

Tension builds, as Charley’s love for Irene starts to interfere with his obligation toward the honor of the Prizzi family. All is resolved in a conclusion you won’t soon forget. This was a movie that was adored by critics, but perhaps less so by squeamish audiences. Though nominated for eight Oscars, including Best Picture, it won only for Anjelica Huston’s supporting-actress turn as Maerose Prizzi, the Mafia princess spurned by Charley and itching for revenge. Sweet revenge for Anjelica too: the talk had been that she was cast in the film only because she was Huston’s daughter and Nicholson’s girlfriend. Turning in a seethingly angry performance, she fooled them all.

John Huston, of course, is long gone now. Jack Nicholson, once Hollywood’s favorite man- about-town, has not been on screen in a dozen years, and rumors fly abut his physical and mental state. Turner’s still working, notably in TV’s The Kominsky Method opposite Michael Douglas, but her svelte shape is long gone and her husky voice is now almost a baritone. Happily, Anjelica too remains active, though a lot of her recent work is in voiceover. Time is cruel in the entertainment biz.