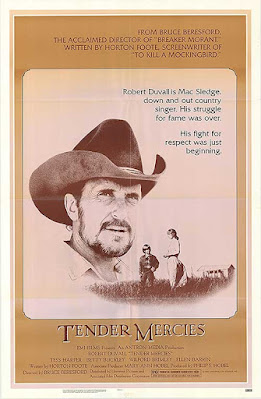

Robert Duvall has long been one of Hollywood’s most respected character actors, starting with supporting roles in such major films as To Kill a Mockingbird (as Boo Radley, 1963), MASH (as Major Frank Burns, 1970) and The Godfather films (as “fixer” Tom Hagen, 1972 and 1974). Unlike most character actors, he ultimately made the leap into leading roles. Having grown up in a military household, he brought aa fierce authenticity to the complex role of Bull Meechum in The Great Santini. In 1981, the part earned him his first nomination as Best Actor, but he was up against such landmark performances as that of Robert De Niro in Raging Bull (the eventual winner) and John Hurt in The Elephant Man. Three years later, though, he took home the Oscar for the role of country singer Mac Sledge in Tender Mercies.

Also

winning an Oscar for Tender Mercies was its writer, Horton Foote, the

Texas playwright who adapted To a Kill a Mockingbird for the screen, and

wrote both the stage and film versions of The Trip to Bountiful. Foote

was a Texas country boy to the tips of his fingernails (though he died in Connecticut),

and he could be relied upon to convey simply and directly a down-to-earth life.

That’s why he was honored by the Academy for a screenplay some might call

slight. (Leonard Maltin’s now defunct but invaluable guide calls it “not so

much a story as a series of vignettes.”) In this particular Foote project,

apparently written with Duvall in mind, the central character is a noted

country-western singer, now on the skids, who finds resurrection in the home of

a young widow running a motel and filling station in the middle of nowhere.

Country western is not my music of choice, but my colleague Diane Diekman has made a career out of exploring the lives of country music stars like Marty Robbins and (upcoming) Randy Travis. I’ve read her Live Fast, Love Hard: The Faron Young Story, about a singer whose considerable talent was eclipsed by his outrageous lifestyle, and I think I have some sense of what stardom can do to dirt-poor country boys. The norm for Young and others, when at the height of their powers, seems to have been fast cars, hot women, and cold brews, with a firearm or two thrown in for good measure. Duvall’s Mac Sledge is first seen as a down-and-out drunk. But his gentle connection with Vietnam widow Rosa Lee and her scrappy young son brings out the best in him. Through them he learns to live again, to forget the bitter marriage he’s fleeing, and to find comfort in family and faith.

That last is key: Robert Altman had it right in Nashville (1975), in which the film’s many interpersonal struggles are forgotten on Sunday morning when everyone turns out to praise the Lord. In Tender Mercies (the title comes from a bedtime prayer that Rosa Lee fervently recites), old-time religion becomes a counterweight to the heavy burdens Sledge sees himself carrying. By the film’s end, despite it all, he’s returning to the music he loves. And, even more important, he’s finally able to see himself as a happy man. Yes, he still mistrusts the notion of happiness, all too aware that bad things can happen to good people. Still, he’s now finally able to accept the positive taspects life and move on.

This isn’t a great film, but it’s anchored by a great performance. However plodding and predictable the action might be, Duvall keeps us connected with life as it is lived.

At a time of many religious holidays (Passover, Eastern, Ramadan), I wish all my readers well. Special thanks to Diane Diekman for helping me see the glories of country music. Write to her at djean@midco.net if you’d like to be added to the mailing list for her comprehensive country music newsletter.

This movie speaks to me. I've felt the barronness life can become and you see that barronness in the location and feel Mac's emptiness. I love a good redemption story and this is one of my favorites. The Family Man is another favorite. Tender Mercies is short on dialogue but the emotions are delivered very effectively through great acting. I love when Mac overcomes his fear of failure the night he sings his song at the dance hall/bar to an enthusiastic reception. It was sad to see his daughter die so young, and I couldnt help but think his ex wife with her bitterness for Mac and smothering of their daughter helped drive their daughter to her tragic end. I love the movie and watching the characters work through the issues at hand and head into a brighter future.

ReplyDeleteMany thanks for chiming in. I hope you return to Movieland again soon!

Delete