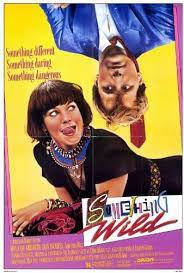

Ever since the untimely death of Ray Liotta four months ago, I've been trying to get hold of Liotta’s 1986 breakout performance in Jonathan Demme’s Something Wild. Three years before he played a ghostly Shoeless Joe Jackson in Field of Dreams, four years before he went to the mattresses as Henry Hill in Goodfellas, Liotta was indelible as a former high school classmate of Melanie Griffith’s Lulu, a man with a hair-trigger temper and a great enjoyment for mayhem. He must have made quite an impression on my fellow movie-lovers. When—after his death at age 67--I started requesting the film from my local library, it took four months for it to end up in my DVD player.

It was worth the wait. After Hours, shot by Demme in 1986, is described online as an “action comedy.” But that designation doesn’t begin to suggest the film’s antic impact. At first it’s indeed very funny, showing a Wall Street financial nerd (Jeff Daniels) who can boast a big and very recent promotion falling under the spell of a gaudily-dressed party girl, played by Melanie Griffith (she of the babyish voice and the body that just won’t quit). This mismatched pair embarks on suburban adventures that feature alcohol, handcuffs, reckless driving, and thrill-seeking of all varieties. But just when we’re thoroughly enjoying their unlikely fling, the tone of the movie starts to shift dramatically. Griffith’s Lulu is not quite the carefree gal she seems to be, nor is Daniels’ uptight yuppie entirely telling the truth about his own placid homelife. And then there’s Liotta, showing up as Ray Sinclair at Lulu’s Pennsylvania high school reunion. Ray is handsome, charismatic, and alarmingly volatile, and when he appears the movie takes a left turn from which there’s no going back.

It was Demme’s goal, at this fairly early point in his directing career, to try to meld screwball comedy and film noir. His bold experiment with a midpoint shift in tone made me, when I first saw the film, slightly queasy. This time around, I enjoyed Demme’s directorial sleight of hand for what it was. The film is a wild ride, and its unpredictable quality—in an era when we can generally figure out what’s coming next on our movie screen—now strikes me as hugely refreshing. I don’t always agree with the late Roger Ebert, but I love his description of Something Wild: “This is one of those rare movies where the plot seems surprised at what the characters do.” Exactly right!

One of the most memorable aspects of Something Wild is the role played by Griffith’s costumes and hair stylings. Clothes, in this film, do make the man . . . or, in this case the woman. The sexy vagabond of the early scenes—with her brunette bob and her jangling jewelry—is suddenly transformed, later in the film, into a honey blonde who favors toned-down makeup and prim white frocks. Lulu’s costume changes signify the revelation of the various layers of her complicated psyche. There’s one more major costume shift at the tail-end of the film. It’s a final twist that many critics find arbitrary and not needed, and I think they’re right. But that’s the challenge of a script as eccentric as this one: knowing when to stop.

The film’s score ranges from the classic to contributions by such pop icons as Laurie Anderson and David Byrne. Unsurprisingly, the featured track is “Wild Thing,” performed in various versions. .A hip surprise is the cameo appearances by indie iconoclasts John Waters and John Sayles. They too can be considered something wild.