What makes a Pedro Almadóvar film so exciting is that, while watching it, you don’t always know where it’s going. Not for him the tidy formulaic structure (set-up, complication, climax, resolution) prescribed by screenwriting gurus. Instead, he deals in juxtapositions and surprises. But the biggest surprise generally comes at the end, where you suddenly realize what his intentions have been all along.

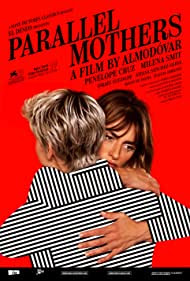

His latest, Parallel Mothers (Madres paralelas), is succinctly described as “the story of two mothers who give birth the same day.” This focus on mothers and babies is accurate, as far as it goes. It also puts this film in line with others in which Almadóvar focuses his gaze almost exclusively on the female of the species. It’s hard to think of other male directors who’ve devoted themselves so intensely to exploring the lives of women, in all their complexity and beauty. See for instance All About My Mother (in which a trans woman is part of the cast of characters) and Volver. Both of these films feature an Almadóvar favorite, the luminous Penélope Cruz, who stars in Parallel Mothers as the mother of a newborn. For her vibrant performance as Janis (named after Janis Joplin by her hippie mom), she was recently nominated for a Best Actress Oscar.

It's curious, come to think of it, that motherhood looms large in this year’s Best Actress category. In Being the Ricardos, Nicole Kidman plays Lucille Ball as the mother of a young child, one who is dealing with a second pregnancy while her career and her marriage hang in the balance. (Alas, none of the material pertaining to the new pregnancy, is either accurate or convincing.) In Spencer, Kristen Stewart as Princess Diana survives a holiday weekend from hell partly because her young sons are nearby. Olivia Colman in The Lost Daughter can’t get past her own parental failures of many years before. By contrast, Cruz plays a new mom, older than most, who throws herself joyfully into the obligations and delights of tending an unplanned baby. It’s only several very unexpected twists of fate that turn her world upside down, leading her into a moral dilemma she (and we) didn’t see coming.

But this is not only a film about motherhood. It’s also, though more subtly, about being a daughter: both Janis and the very young roommate with whom she bonds at the maternity hospital have reason to feel cheated out of a mother’s embraces. And there’s another key strand, one that begins the drama, then seems to disappear, before re-emerging powerfully at the end. The film kicks off with Janis persuading a noted forensic anthropologist to take an interest in her home village, where a clutch of husbands and fathers were massacred by Fascists, then dumped into an unmarked grave. The women of the village are desperate, after more than a half-century, to reclaim the bodies of their loved ones and given them a proper burial. Thanks to the efforts of Janis, the work is begun. Which leads to a conclusion that not only underscores what Franco’s goons has done to the people of today’s Spain but also drives home the underlying motif through which Almadóvar binds disparate plot strands together. It’s a matter of family ties, of inheritance passed on from the old to the young, of the moral values as well as the genetic materials that connect generations. Strong stuff, this. The solemn but joyous uniting of all the film’s major characters in the film’s final scene suggests that Almadóvar, for all the gloom of his story’s details, is able to look forward with hope.