Friday, April 27, 2012

Leaving Las Vegas, Bollywood-Style

With Bollywood movies, you get your money’s worth. A friend has reminisced to me about his moviegoing childhood in South India. When a new film came to his village, young and old turned out to see it. They gathered in a thatch-roofed hut and sat mesmerized for hours. Even a downpour couldn’t spoil the fun.

An Indian movie contains something for everyone. If you like low comedy, or high drama, or brutal action, or social message, or elaborate song-and-dance numbers in spectacular costumes, a Bollywood film will give it to you in large doses. A sophisticated mixture of all these elements (as pungent and complex as a good Indian curry) made the Bollywood-inspired Slumdog Millionaire a crossover hit. When a screenwriting student of mine, Danish Renzu, found out I enjoy Bollywood, he lent me a copy of Devdas. It’s over three hours long, and there’s never a dull moment.

Devdas is based on a 1917 novella of the same name. It’s been filmed three times, and the full-color version I saw was, when released in 2002, the most expensive Indian movie of all time. Starring Sharukh Khan and the impossibly gorgeous Aishwarya Rai, it’s a Romeo and Juliet tale in which family snobbery and class distinctions trump true love. Devdas tells of a nineteenth-century world in which the sons of landlords shouldn’t lower themselves to love the daughters of dancing girls, even if they have grown up side by side. In Devdas, the rules of society are strict, and patriarchs hold sway even over grown children who have spent ten years studying abroad. Still, the film shows us an environment in which passion throbs. (This is hardly surprising, given that romantic ardor -– like that of the god Krishna for Radha –- is entwined in Hindu theology, and the ancient carvings of Hindu temples like Kajuraho are so erotic they can make you blush.)

True to the Indian tradition, Devdas has its share of romance-novel elements, like the lovers deliciously entangled in a flowing stream in the rain. He tenderly kisses the sole of her foot, but there’s absolutely no lip-locking. And, of course, no sex. Though the plot hinges on a courtesan ensconced in a brothel, raw intercourse is never suggested. The film’s most flagrant moment comes when a secondary character makes advances toward her, saying something on the order of “Can I unscrew your nose ring?”

That brothel, by the way, is both clean and exquisitely appointed, as is every set in this film. India, in Devdas, is a place of fire and water. There are thousands of glowing candles, an oil lamp that’s never to be extinguished, and a raging conflagration, when the hero stops sulking long enough to try burning down the family mansion. There are also countless gallons of water, in the form of streams, rivulets, lakes, and lots and lots of tears. But the plot’s major turning-point comes when Devdas forsakes water for alcohol, responding to the loss of his love by going on an epic binge. He’s a depressive sort of drinker: once he gives up his high-class teetotaling ways for a bottle of rotgut, he seems determined to do himself in. In the film’s big finale, he has himself delivered to the gates of his love, who’s been married off (though still remaining virginal) to an aristocrat. As he expires, her name on his lips, she’s running wildly through the corridors of her palace, her veils floating behind her, to reach his side. Will she make it in time?

So much emotion, so much hootchy-kootchy. Western movies seem a bit pallid by comparison.

Monday, April 23, 2012

Wynorski and Corman: Screaming All the Way to the Bank

Devoted reader Craig Edwards has requested the story of how schlockmeister Jim Wynorski (whose next low-budget release is Gila!, about the attack of a giant lizard) got his start in Hollywood. So I’ve cribbed from my Roger Corman: Blood-Sucking Vampires, Flesh-Eating Cockroaches, and Driller Killers the following run-down of Jim’s unparalleled career. Mr. Craig, this one’s for you!

Jim Wynorski, once who told Time Magazine that “breasts are the cheapest special effect in our business,” was born to thrive in the giddy environment of Roger Corman’s New World Pictures. Corman was already a hero to Jim when, as a young man with an advertising background, he visited Roger’s wife Julie to pitch some story ideas. He walked out with a job as New World’s head of marketing, and from then on he was a Corman regular. As he told me, “I got caught up in it so fast, it was like a twister coming by. That’s the world an impatient person like me loves to work in. Because it’s instant gratification.”

Wynorski’s first big success came when, on a $40 budget, he re-cut the trailer for an unsuccessful Italian-made New World horror film called Something Waits in the Dark (1979). Wynorski’s trailer, which lured ticket-buyers with the promise of seeing “a man turned inside out,” incorporated new footage of “this guy running around, covered with slime, all his veins hanging out, chasing a girl in a bikini.” The film, re-titled Screamers, opened in Atlanta on a Friday. Early Saturday morning, Corman phoned Wynorski and demanded that his new material be edited into the film itself. He needed to appease the disappointed audiences who “rioted in the drive-ins last night, tore out the speakers, tried to lynch the manager.”

After Corman spotted Jim’s gift for tapping into the male subconscious, Jim was put to work concocting scripts that featured action, comedy, and women without clothing. Before long, he was also a director. Wynorski’s exuberant “Let’s-Put-On-a-Show” approach is especially evident in the making of Sorority House Massacre II (1990), also fondly known as Nighty Nightmare. It seems that the house sets from Slumber Party Massacre III had been left standing at the Concorde studio. On a Friday afternoon in late May, Wynorski secretly got Julie Corman to stake him $150,000. He spent three days writing a quickie slasher flick, and two more days casting actresses who were game, well-endowed, and not members of the Screen Actors Guild. By Friday, with the Cormans out of town for Memorial Weekend, Wynorski was shooting. The following Wednesday, Corman finally discovered what was going on. He saw the finished product, recognized its commercial potential, and said, “Jim, I want you to make this film again. Use the same script, use the same cast.”

Because the original sets were now gone, this follow-up took place in an office tower, fictional home of the Acme Lingerie Company. It was called Hard to Die, and fans like critic Joe Bob Briggs celebrate its excesses: “Sixteen breasts. Twelve dead bodies. Hot pants. Tube tops. Denim cutoffs. Camisoles. Bustiers. Bimbos drenched by fire sprinkler system for an extremely apparent reason. Neck-cracking. Multiple splatter. Gratuitous flashback footage from Slumber Party Massacre.” Corman was delighted by this seat-of-the-pants moviemaking, which reminded him of his own early days. Wynorski is convinced that he and Roger share the same film aesthetic: “Big chase and a big chest. That’s the formula.” Says filmmaker Joe Dante about the unlikely pairing of the dignified Corman and the outrageous Wynorski: “Jim Wynorski is the side of Roger that he may have inside, but he never lets anybody see.”

Friday, April 20, 2012

Clara Bow, Unmiked

In 1952, Singin’ in the Rain treated Hollywood’s shift from silent movies into talkies as comedy. In the past year, The Artist made the same evolution seem poignant (for the stars left behind), but also hopeful and romantic. I just caught up with David Stenn’s Clara Bow: Runnin’ Wild, which drives home the point that for many connected with the motion picture industry, the early days of talkies were absolutely terrifying.

Stenn is known as a Hollywood type himself. He has writing credits on such TV favorites as Hill Street Blues and Beverly Hills, 90210, and he’s currently a supervising producer on Boardwalk Empire. But his two acclaimed biographies show where his heart really lies: with the golden girls of the silver screen. I haven’t done more than dip into Stenn’s Bombshell: The Life and Death of Jean Harlow. I do know that it, like the Clara Bow book that preceded it, was edited (with erudition and flair) by a golden girl of my own day, Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis. It’s clear that Stenn gravitates toward savvy beauties who’ve known tragedy and trauma.

Clara Bow survived a harrowing childhood to become one of Hollywood’s top stars. As the “It” Girl of silent films, she brought to the screen an all-American sex appeal that was something new. Before Clara, says Stenn, “depictions of flagrant female sexuality were of foreign and hence decadent origin.” Clara, though, combined sensuality with a “fresh and natural” quality that set her apart from the sort of “jaded and blasé foreigner” who vamped in the early silents. For her many fans, Clara was the Roaring Twenties personified.

It’s not true that Clara fell from favor in the sound era because her voice wasn’t suitable. As sound technology advanced in the 1930s, the public learned to appreciate vocal variation, looking with favor on Jean Harlow’s midwestern twang and Jean Arthur’s “foghorn voice.” Stenn tells us that Carole Lombard found stardom despite “breathless delivery and half-swallowed words [that] would have recorded as gibberish in early talkies.” As for Clara, especially when scenarios permitted her to sound like the blue-collar Brooklyn gal she was, she could still prove effective in sound features.

But the advent of sound was a frightening time. Cameras became much heavier than silent-film cameras, which meant that actors’ movement was severely restricted. Performers were instructed to speak in a monotone, and warned that heavy footsteps would echo. Because air conditioning made too much noise, sets were sweltering, with hot studio lights melting actors’ makeup. The new sound engineers briefly ruled Hollywood, dismissively scrapping takes that were “no good for sound.”

Clara Bow, who loved to move freely on a movie set, felt severely hampered. She developed a severe case of “mike fright,” and couldn’t stop herself from frequently glancing up at the microphone overhead. As she lost confidence in her own abilities, her career ground to a halt. She made her last movie in 1933, but lived on for 30 years, remembering her past glory. In later life, she became an admirer of Marilyn Monroe, who wanted to portray her on screen. But the two Hollywood sex symbols were too insecure ever to meet in the flesh.

David Stenn will appear on my panel at next month’s Compleat Biographer Conference, sponsored by BIO (Biographers International Organization). The date is Saturday, May 19, the place is USC’s Davidson Conference Center, and the topic is “How Dare You? How to Research the Unauthorized Celebrity Bio and Live to Tell the Tale.” Other speakers include Andrew Morton, author of Diana: Her Story. The public is invited. Come one, come all!

Tuesday, April 17, 2012

The Anderson Platoon: Boots on the Ground

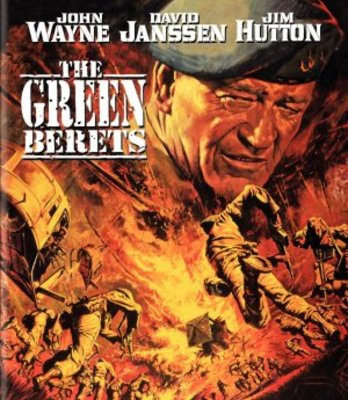

Why should I care about Pierre Schoendoerffer, the French filmmaker who died last month at age 83? His is hardly a household name. Few Americans will have heard of his films, which often deal unflinchingly with combat in Indochina. But one of them, The Anderson Platoon, copped an Oscar as best feature-length documentary of 1967. At a time when Americans were just waking up to the realities of the Vietnam War, Schoendoerffer gave them a picture -- up close and personal -- of what was happening to the grunts on the ground. It was a far cry from John Wayne’s flag-waving Vietnam epic of the following year, The Green Berets.

Schoendoerffer (unlike John Wayne) came by his knowledge of warfare honestly. Though he’d completed his own military service, he volunteered in 1951 to serve as a cameraman in Indochina, where the French were fighting to retain control of their former colonial empire. After three years, and a wound that landed him in a Saigon hospital, he finagled permission to parachute into Dien Bien Phu, site of a decisive battle that ended in the rout of the French by Vietnamese forces. Intending to chronicle the war, he found himself captured, threatened with execution, and marched hundreds of miles to a Vietnamese-run prison camp. Four months later, he finally won his release.

You might think Schoendoerffer would have had enough of Southeast Asia. But, as he said, "The earth of Indochina still clings to my soul, just like the mud of the trenches used to stick to my boots.” His 1965 film, The 317th Platoon, depicted fictive French soldiers and their Laotian allies trekking through the jungle. One year later, when American troops had replaced the French in Vietnam, Schoendoerffer returned to the country’s central highlands to capture in cinéma vérité style the daily doings of an American infantry platoon led by Lt. Robert Anderson, a black graduate of West Point. In the fall of 1966, the troops are shown as still largely optimistic—and the racial tension that will plague American units later in the war is virtually absent.

Schoendoerffer’s camera captures the platoon’s life in all its minutiae: soldiers taking communion; playing a gambling game; grappling with homesickness on an aimless trip to Saigon. But there’s the stuff of war too. Platoon members, mostly draftees, go on patrol; engage in firefights; uncover homemade Viet Cong weapons; try to live through missions whose goal eludes them. Along the way, some men get wounded, and a few of them die. After they’ve helped treat an injured local girl, one soldier sings a haunting blues dirge, “The St. James Infirmary,” and several others get tears in their eyes. “The St. James Infirmary” returns on the soundtrack at the close of the film, as a badly wounded black man clasps the hand of his white buddy before being evacuated by air. The film ends with a sunset silhouette as the men of the Anderson platoon watch the chopper, carrying its precious cargo, rise into the sky. A far cry from the hopeful dawn with which John Wayne would conclude The Green Berets, this sunset seems to portend nothing good. As narrator Schoendoerffer sadly notes, “The platoon is only a small pawn in a big game.”

Unlike The Green Berets (so grossly inauthentic that soldiers who saw it in ‘Nam used to throw beer cans at the movie screen), The Anderson Platoon conveys the unmistakable whiff of truth. Studiously unsentimental, it nonetheless brings home the meaning (and the meaninglessness) of the Vietnam conflict, one in which stoicism is a valuable trait but tough-guy heroics have no place.

Friday, April 13, 2012

Dennis Palumbo: A Shrink Who’s No Shrinking Violet

Some people say that anyone who seeks a career in Hollywood should have his head examined. Dennis Palumbo knows all about that, having experienced show biz from both sides of the couch. Starting in 1976, he wrote for several TV series (including Welcome Back, Kotter and The Love Boat), then earned story and screenplay credits on the Peter O’Toole comedy classic, My Favorite Year. After laboring in the entertainment industry for 16 years, and benefiting from the psychotherapeutic process as a patient, he decided to enter the field. Today he’s a practicing psychotherapist who specializes in treating creative types: writers, actors, directors, and producers.

Dennis writes “Hollywood on the Couch” for the Psychology Today website, and is the author of Writing from the Inside Out, a book that several of my students have found helpful in combatting writer’s block. In his spare time, he publishes mystery novels (Fever Dream is the latest). None of this was how his life was supposed to go. But a movie changed everything.

At age seventeen, Dennis saw The Graduate, and was deeply struck by that poolside scene in which Benjamin Braddock is advised that the future lies in plastics. The point, of course, was about parental expectations for their children’s worldly success. Dennis himself was then heading for college and an engineering career: “I was the first of nine grandchildren, and I was gonna be doctor, lawyer, engineer, or – as a fallback position – priest. Those were my four choices.” When he saw Ben reluctantly descend into his parents’ pool in his gift SCUBA gear, “That’s how I felt. I felt like I was drowning, because I didn’t want to be an engineer.”

Says Dennis, “When your patients are creative people struggling to justify wanting to be writers and directors and actors, as opposed to what their parents wanted them to be, The Graduate comes up all the time. Because Benjamin challenges the conventional wisdom of what he should do with his life.” But non-Hollywood types also feel the impact of moviegoing: “For the average person a movie can change their life, if only by illuminating things that make them feel they’re not alone, or reinforcing things that have [been] niggling under the surface. They see the film and they say, ‘Gee, y’know, I am allowed to get divorced,’ or ‘It is possible to leave a small town.’ Or ‘A black guy can be a hero,’ or ‘Your girlfriend can be Chinese.’”

Or, of course, “You can trade in a writing career for a fulfilling life as a psychotherapist.” Curiously, as Dennis points out in a recent column, movies currently reveal a changing view of the whole psychiatrist profession. Once upon a time, therapists were kindly paternal figures like Claude Rains in Now Voyager and Lee J. Cobb in The Three Faces of Eve. Today, they’re apt to be rapists, murderers, and even cannibals (see The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo and The Silence of the Lambs). And Dennis’s hair-raising piece doesn’t even mention Michael Caine’s role as a cross-dressing psycho(therapist) in Dressed to Kill.

Because Palumbo sees therapists as getting a bad rap at the movies, his mystery novels feature Dr. Daniel Rinaldi, a psychologist who sleuths for the Pittsburgh police force. Rinaldi, haunted by past tragedies, has had his share of personal trauma. But though he’s sometimes ornery and temperamental, he remains, in Dennis’s words, “someone trying desperately to make a difference. To help others on the path to healing, even if only as a way to come to some kind of peace himself.” In short, he’s a great character for a movie.

Tuesday, April 10, 2012

Food for Thought at the Movies

‘Tis the season to be eating. If you’re a Christian, you’ve probably just scarfed down a big Easter ham, or at least – let’s be honest – some marshmallow goodies brought by the Easter bunny. If you’re Jewish, you’re eating matzoh (and more matzoh). And down the street from me, the food trucks are blooming. These days L.A. is becoming a true moveable feast, with Korean BBQ trucks vying for space with vehicles vending Indian roti, Hawaiian spam-on-a-stick, kimchi quesadillas, and Philly cheesesteak. Today I even spotted a truck touting Trailer Park cuisine. You wait for your order (for Chicken & Waffles or Frito Pie) on an Astroturf rug, surrounded by plastic pink flamingoes. John Waters would definitely approve.

Food and movies just seem to go together. If you attend stage productions, even toting a water bottle to your seat seems like a violation of etiquette. But at the movies you’re expected to chow down, maybe with a tub of popcorn and a supersized cola. Some upscale cinema venues will even deliver to your seat a small meal, or perhaps a cocktail. All that chewing could prove distracting to the person beside you, especially if you’re watching a film about starvation, like The Pianist. And if you’re munching on a meat pie, you’re certainly adding a new dimension to someone’s enjoyment of Sweeney Todd.

Most of us find cooking magical, especially when someone else is doing it. If that someone is trained in the culinary arts, the effect can be poetry in motion. That’s why there’s a long history of movies about the expert preparation of food. Ang Lee’s Taiwanese film about a master chef and his lovelorn daughters, Eat Drink Man Woman, was so scrumptious that it spawned two knock-offs: Tortilla Soup and Soul Food. Equally mouth-watering is Stanley Tucci’s Big Night, involving Italian-American brothers trying to save their foundering restaurant by serving up, for one night only, a spectacular feast. Speaking of feasts, I can’t overlook a tantalizing Danish film, Babette’s Feast, in which a poor French refugee eking out a frugal life in an austere Danish village comes into a sum of money, and puts it toward the preparation of a magnificent repast

Food can be sexy too, never more so than in Chocolat, where Juliet Binoche (playing a mysterious candy maker who wafts into a small French town) proves that the best way to a man’s heart is via his sweet tooth. (I suspect that Julia Child will never be considered a sex symbol, but Meryl Streep certainly kept movie spouse Stanley Tucci happy in Julie and Julia.)

But for me the yummiest, yuckiest, wackiest food movie of all time is Juzo Itami’s Tampopo, which was described in press releases of the day as Japan’s first ramen western (akin to a spaghetti western – get it?) The plot involves two drifters who come upon a desolate roadside eatery and get involved in the life-or-death quest to create the world’s best noodles. But we cut away at times to odd vignettes involving food (and sex), food (and social class), food (and kinky fetishes). The movie ends, as I recall, with a lingering closeup of a young mother nursing her baby in a public park. After all the eating oddities that precede it, an infant’s hungry sucking has never seemed more profound.

Writing this has made me hungry. And it has also given me a lucrative idea. How about a kosher-for-Passover food truck featuring matzoh brei and stewed prunes?

For Hilary Bienstock Grayver, who is devoted to feeding her family, in any season, by any means necessary.

Thursday, April 5, 2012

James Cameron Goes On and On

It’s tempting to say that James Cameron gives his fans that sinking feeling. After all, he recently descended to the bottom of the Marianas Trench, in a submarine of his own devising, to explore the ocean at its deepest point. And his very biggest hit – one of the most popular movies of all time – is his dramatization of the sinking of the Titanic. With a new 3-D version of Titanic now coming into theatres, it seems high time to remember where Cameron’s career began. With, of course, Roger Corman.

I never met Jim Cameron, but I’ve spent many hours with Randy Frakes, an effects specialist turned screenwriter who had been one of Cameron’s college pals. The two wangled their way onto a Corman low-rent sci fi epic, Battle Beyond the Stars (1980), by promising to build a front projection camera rig for inexpensive special effects shots. When the gizmo was finished, Roger declared himself unconvinced, but Jim rebounded into the position of model maker, then became the film’s art director, devising sets out of little more than foamcore, hot glue, gaffer’s tape, and spraypaint. He had everyone collecting Styrofoam containers from McDonald’s hamburgers: when spraypainted silver, these certainly looked impressive lining the walls of a spacecraft corridor. But if an actor happened to turn around carelessly, the whole thing would crumble. Then it was back to McDonald’s for more Big Macs.

Cameron’s ambitious sets for Battle Beyond nearly killed him, because he micromanaged every detail. Randy remembers, “He hardly ever slept for six weeks straight.” Afterwards, Jim and Randy tried pitching script ideas, but their concepts were always too grandiose for the low-budget Corman environment. Still, because Roger admired Jim’s ability to think on his feet, he was invited to direct second unit (including a “maggot rape scene”) for Galaxy of Terror, and went on to make his directing debut with Piranha II.

At New World Pictures, Jim Cameron found a career, and also something more. During the frantic pre-production days for Battle Beyond, work went on at Corman’s Venice studio nearly around the clock. One day assistant production manager Gale Anne Hurd was going over costs and schedules with Jim, the new art director, when they heard a piercing scream. It seems a crew member kneeling on the floor had stuck a matte knife in his pocket, its blade protruding. A second man had tried to step over him, but the unseen blade caught his leg, severing his femoral artery. Blood spurted dramatically; he was convinced he was going to die. Gale told me, “Jim had the presence of mind to take his shirt off, make a tourniquet, tie it, and we both drove him to the hospital.” Jim’s low-key heroics obviously caught the attention of this capable young woman. A few years later, the two were married.

As a couple they collaborated on a futuristic film of their own, The Terminator. Gale also produced such later Cameron films as Aliens and another watery epic, The Abyss. Somewhere along the line, the two deep-sixed their romantic relationship. But they remain friends, and also fans of Roger Corman. When Jim accepted his slew of Oscars for Titanic, Gale was disappointed he didn’t single out Roger in his thank-yous. Wouldn’t a talent like Cameron have succeeded without New World Pictures? As Gale insisted to me, he “wouldn’t have gotten a foot in the door, I don’t think. To go from being a guy building spaceship models to art director to second unit director in those three steps, that doesn’t happen anywhere else.”

Sunday, April 1, 2012

Starbucks and Big Bucks for Screenwriters

Some weeks ago, a friend with ties to the film industry wrote to me, very upset, regarding a new Starbucks policy she’d read about online. She sent me the article in question, which opened with the news that “Starbucks, the international coffee company, announced today that it is banning all screenwriters from its 19,435 locations worldwide, effective immediately. The move comes after a study commissioned by the company revealed that screenwriters not only spent the least amount of money at their coffeehouses, but they also have ‘a depressing and desperate air about them that spoils everyone else’s experience.’” Screenwriters are also prone, apparently, to stealing packets of Sweet ‘n’ Low. The piece went on to quote Chris Keyser, president of the Writers Guild of America, who vowed to fight the ban on his union’s behalf.

My friend expressed her outrage at the unfairness of it all: “I have to wonder about the study methodology. Did they do an exit poll asking for a WGA membership card from the screenwriter with bulging pockets of Sweet ‘n’ Low?” Her point, I gather, was that it’s wrong to lump together card-carrying screenwriting professionals with wannabes who hang out at Starbucks. At least where I live, it’s hard to find a Starbucks table occupied by someone who’s NOT working on a screenplay.

Then there’s me. I don’t write screenplays at Starbucks. But I read scripts, comment on student scripts, prepare for talks about screenwriting, and sometimes huddle with filmmaker-types to work on projects. Meanwhile, half the people around me seem to be wrestling with character arcs and second-act turning-points. The rest are probably eavesdropping on one another’s chatter, trying to come up with dialogue that sounds fresh and real. And in a town where so many waiters are struggling actors (you should hear them emote while reciting the nightly specials!), it’s easy to assume that a good percentage of the baristas – while whipping up your half-caf extra-hot soy latte – are simultaneously trying to compose a snappy logline.

Doubtless most of these Starbucks-based writers are not WGA members. But that doesn’t mean they have no (extra) shot at success. At New World Pictures, back when Roger Corman was a WGA signatory, we all learned how to dodge around Writers Guild regulations to save money. In my Concorde-New Horizons years, the idea was to hire only non-union writers, but many WGA members were so desperate for a paying gig that they’d happily write a Corman quickie under an assumed name. One up-and-coming writing team combined their middle names into a catchy pseudonym to affix to the thrillers they cranked out for Roger. There was a time when “Henry Dominic” earned far more money writing for Corman than the duo did on their mainstream projects, but that was long ago. Like such Corman nobodies as Robert King and Paul Haggis, they've since gone on to fame and fortune. My point? Don’t count anyone out.

My husband the engineer mentioned at a dinner party that a Hughes Aircraft colleague was an aspiring screenwriter. For years this fellow had been taking classes, reading how-to books, writing spec scripts. Eventually he quit Hughes to try to make it in Hollywood. We all smiled at such naïveté, until the would-be writer’s name was mentioned. Then a Corman friend of mine gasped, and noted that the former engineer was now getting the big bucks for writing well-engineered TV dramas.

That Starbucks ban on screenwriters? I have a strong hunch it was somebody’s early April Fools joke. Now excuse me, please -- I’ve got a date with a for-here tall non-fat extra-foamy latte.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)