Once upon a time, John Carpenter was not well known. As a grad student studying at the USC school of cinematic arts, circa 1974, he was working on a 16mm thesis film with an outer-space setting. Most of the action took place in the cockpit of a deteriorating starship searching the cosmos for unstable planets. The bargain-basement budget (about $6000) of the original Dark Star was part of its charm. It was funny enough, and appealing enough, to catch the eye of Hollywood’s money men. That’s why the student film, following some major edits, was turned into a commercial feature, and Carpenter’s professional career was born.

I focus on Dark Star because the guy to whom I’m married still bears a small grudge. As a young engineer who liked to tinker, he was persuaded to build the console of the movie’s command center out of craft-store plastics and electrical switches. His efforts were much appreciated by Carpenter, who promised him a screen credit for his efforts. He also lent the production $50. You guessed it: once Carpenter went Hollywood, the promises didn’t get kept. This despite the fact that once he launched a little movie called Halloween in 1978, Carpenter was the hottest thing going in the horror genre.

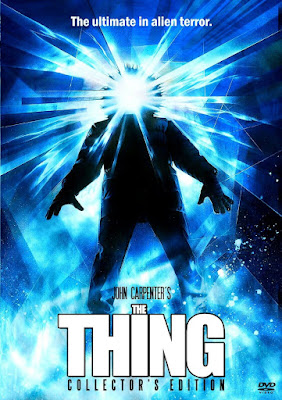

But Carpenter’s well-documented stinginess shouldn’t detract from his talent. Horror is hardly my favorite genre, but—with Halloween approaching—I couldn’t resist checking out one of his creepier efforts, 1982’s The Thing. This film, as I discovered, was hardly an instant hit. Critics were harsh (the Los Angeles Times called it "bereft, despairing, and nihilistic,” while Newsweek said it lost drama by "sacrificing everything at the altar of gore”). Audiences were no more kind. Though Carpenter’s career suffered, the film eventually found hordes of new fans on video. I agree that it’s grim, but also highly creative, with eerie visuals that won’t let go of your imagination.

The origin of The Thing was a novella called Who Goes There? that first made it to the screen in 1951 as The Thing from Another World. Seeing it as a boy, Carpenter was fascinated. Then he read the original version, which posits that an extraterrestrial life-form has come to earth to assimilate, then imitate, other organisms, including dogs and people. As a result of this otherworldly invasion, men who encounter “the thing” are turned into horrible globs of protoplasm who still bear the remains of human characteristics. Part of what fascinated Carpenter, obviously, is the technical challenge of replicating these weirdly evolving and very deadly creatures. The film gives special effects pros like Rob Bottin (a Roger Corman veteran, natch!) the chance to combine chemicals, food products, rubber, and mechanical parts into gelatinous monsters that sometimes replicate the features of the characters whose bodies they’ve invaded. A full $1.5 million of the film’s $15 million budget went into Bottin’s creature effects.

The other attraction of this story is the chance it offers to play out an Agatha Christie-type thriller, with a cast of characters diminishing one by one. The story is set entirely in Antarctica (portrayed here by Alaskan and Canadian snowscapes), among an assorted group of American researchers—a physician, a meteorologist, a biologist, and so on—who live together in a remote waystation. Played by reliable character actors like Richard Dysart, Donald Moffat, Wilford Brimley, and Keith David, they are vividly delineated . . . but it’s never clear who’ll be the next to turn into a monster. We do suspect that star Kurt Russell will endure, but the film’s bleak ending is sure to take us by surprise.

Happy Halloween! I can’t help mentioning that a new Criterion Shelf blogpost saluting Roger Corman’s creepy Poe films mentions my Roger Corman: Blood-Sucking Vampires, Flesh-Eating Cockroaches, and Driller Killers as a “highly recommended” look at the world of Corman.

.