My own memories of Glenn Ford’s lengthy movie career start with a 1956 comedy, The Teahouse of the August Moon, in which he starred as a good-hearted military man dealing with cultural disconnects while stationed in a village in post-WWII Okinawa. (This adaptation of a Broadway hit – featuring Marlon Brando as a wily Okinawan native -- would surely be condemned for ethnic insensitivity today, but in its own era it was widely considered charming.) I got to know Teahouse as a kid, and even appeared in several little theatre productions, with no apparent harm done. But it was only years later that I saw Ford in tougher fare, playing the beleaguered inner-city teacher in The Blackboard Jungle and especially the ambiguously devoted suitor opposite Rita Hayworth in Gilda.

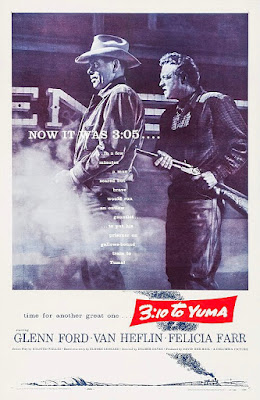

Ford’s son Peter, the product of his troubled marriage to Eleanor Parker, has long been exploring his dad’s legacy. He sees in his father—who was among other things a compulsive womanizer--a dark side that his best roles exploit. Peter’s commentary on the DVD of the 1957 western classic, 3:10 to Yuma reveals that the western was Ford’s preferred movie genre. Having worked for Will Rogers as a ranch hand (while still a student at Santa Monica High School), he was highly comfortable around horses. And 3:10 to Yuma¸ adapted from an early-career story by Elmore Leonard, was one of his very favorites. Leonard is of course far better known for the noirish novels that became movies like Get Shorty and Jackie Brown. But he started out writing western stories for pulp magazines. The kernel of the story that became 3:10 to Yuma involves a rancher, an upright family man. Plagued by drought and the loss of many head of cattle, he accepts a pittance to put a notorious outlaw on a train to the Arizona city where he’s destined to stand trial. The heart of the story, and the film, is the long stretch of time spent in a Contention City hotel room where the outlaw tries to threaten, to cajole, and to bribe the rancher to turn him loose before the train arrives.

According to Peter Ford, his father, then at the height of his celebrity, was first offered the role of the straight-arrow rancher. It eventually went to Van Heflin (who’d played a similar nice-guy role in Shane), so that Glenn Ford could show off his wily charm as the outlaw. You almost believe him when he insists he’s not as much of a troublemaker as his reputation implies. The scenes between the two men in that hotel room do a great job of ratcheting up the tension as, out on the street, Heflin’s supporters melt away out of fear of Ford’s gathering cronies. There’s something of High Noon in the ticking-clock plotting, though good and evil are not nearly so clearly demarcated as they were in that Gary Cooper classic. Among the Ford character’s virtues is a genuine gallantry toward women (there’s a high-octane encounter between him and a pretty but lonesome barmaid played by Felicia Farr). He’s also able to truly recognize the heroism implicit in Heflin’s stubborn insistence on holding to his end of a bargain.

3:10 to Yuma was remade in 2007, with the main roles played by born-again westerners Russell Crowe and Christian Bale. Naturally, the new film featured much more bloodshed and much more corrupt behavior than the original, but critics and audiences seemed reasonably impressed. It was the 1957 original, though, that has found a home in the Library of Congress’s National Film Registry for being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant.”

No comments:

Post a Comment