As awards season heats up, with this year’s Oscars slated to be handed out on March 12, it’s hard to believe that Academy Awards were first presented in 1929, when most movies had not yet learned to speak. The November 1930 ceremony, a swanky shindig held at L.A.’s Ambassador Hotel, gave its biggest prize to the Hollywood adaptation of an anti-war classic, Erich Maria Remarque’s All Quiet on the Western Front. Amazingly, one of ten films in the running for Best Picture of 2022 is the first-ever German language version of this same “war is hell” novel.

At the 1930 ceremony in which All Quiet on the Western Front won its laurels, Greta Garbo’s name was very much in evidence: she competed against herself in Anna Christie and something called Romance. (Norma Shearer took home the statuette.) Anna Christie was also singled out for its direction (by Clarence Brown) and its cinematography (by William H. Daniels, an ace who was still earning nominations in 1964). Daniels’ intimate black-&-white camerawork is one of the glories of Anna Christie, in which the screen is filled with enormous close-ups of some of Hollywood’s most expressive actors. Daniels, of course, had learned his craft in the silent era, and he thoroughly understood Norma Desmond’s rueful remark in Sunset Boulevard: “We didn’t need dialogue. We had faces.”

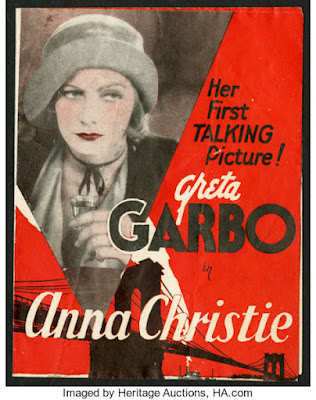

In Anna Christie there are both faces AND dialogue. The most dramatic face, of course, belongs to that scintillating Swede, Greta Garbo, who can be mesmerizing whether she’s projecting world-weariness or joy. Then there’s the beautifully ugly Marie Dressler, as well as George F. Marion as Garbo’s long-estranged father, a frequently tipsy sailor who speaks ominously (and with a colorful Swedish accent) about the allure of “dat Old Debbil Sea.” Both the gritty oceanfront environment and the generally foreboding atmosphere mark this as a play by Eugene O’Neill, who won his second Pulitzer for this early work back in 1922. It's a simple story, but a poignant one. In a rundown wharf-side tavern, Old Chris (Marion) gets word that his twenty-year-old daughter is leaving Minnesota to come stay with him. He fantasizes that she’s a healthy, hearty farm gal, but when she arrives it’s clear that life has been hard on her. Because this was Garbo’s first talkie, Anna Christie was marketed with the slogan “Garbo Talks!” So I’m sure there was some suspense as to what her voice would sound like and what she would say. Spoiler alert: her very first line, after she slumps into the bar-room with a suitcase in tow, is this: “Gimme a whisky, ginger ale on the side, and don't be stingy, baby!"

Though Old Chris remains blind to his daughter’s travails back home, it’s quickly clear to the audience that Anna has faced her own rough seas. She hints at abuse by a family member, and it’s obvious that her “job” in the Twin Cities involved prostitution. Still, she forges a relationship with Old Chris, and they manage to live with some contentment on the coal barge of which he’s now captain and crew. But when they rescue some sailors adrift on the open sea, love comes into the picture., and Anna is challenged to open her heart to the possibility of happily-ever-after. Far be it from me to give away O’Neill’s ending.

Trivia time: There’s a second Garbo version of Anna Christie, shot in German with a largely different cast for the European audience. (“Garbo spricht Deutsch!”) A 2018 opera exists too. And, remarkably, in 1957 the play was turned into a Broadway musical, innocuously called New Girl in Town.

No comments:

Post a Comment