I admit that in real life I’m not a great fan of Johnny Depp. I’ve never been anywhere near him, but his reported behavior toward his fellow human beings (including ex-partners) is not endearing. My hackles were raised when I read in my local paper about his fury at some Sunset Strip developers. As I recall, he threatened a lawsuit against them. After all, they had dared to put up high-rise towers that would mar one corner of the panoramic view of Depp’s children when they played in their Hollywood Hills backyard high above Sunset Blvd. Not that I don’t appreciate unfettered views, but I refuse to worry about the aesthetic pleasures of Depp’s offspring.

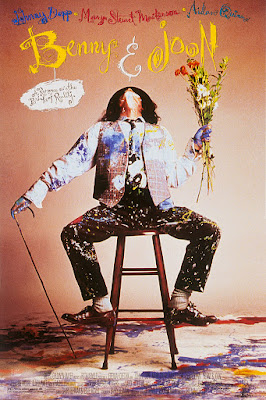

There’s no denying, though, that Depp is a major talent, especially in roles of a whimsical nature. His physical dexterity, coupled with a strong sense of unworldliness, helped him break through to fame and fortune in such unique early roles as that of the title character in Edward Scissorhands (1990). Three years later, though he didn’t play a title role in Benny & Joon, his performance was what you carried away from a film whose primary relationship is that between a tense young mechanic (Aidan Quinn) and his mentally disturbed sister (Mary Stuart Masterson). After their parents’ tragic death, Benny has devoted himself to Joon’s well-being, thus inadvertently stifling the emotional development of them both. Joon’s creative rebellions make their lives together disconcerting: early on, after a frustrated housekeeper quits, Joon (wearing a SCUBA mask) is found by the local police directing downtown traffic with a ping pong paddle. Clearly, something has to give.

That’s when Johnny Depp’s Sam comes into the picture. An unwanted relative who’s come to stay with one of Benny’s poker buddies, he ends up tending Benny’s house while also keeping an eye on Joon. His methods are unorthodox: he uses a skateboard to help clean the walls, and a steam-iron to toast cheese sandwiches. None of this is surprising for someone who seems to have modeled himself on Buster Keaton and the silent movie clowns of the past. It’s not long before the two misfits fall in love, and of course complications arise quickly. At one point, Joon is about to be confined to a mental hospital, barring both Benny and Sam from her life. But, since this is fundamentally a romantic comedy, all problems (along with the cheese sandwiches) are ironed out well before the two-hour mark.

I’m sure books can be written about the movies’ handling, over the decades, of mental illness. In popular films of my youth, like 1962’s David and Lisa and 1966’s King of Hearts, those with mental challenges are gentle souls who are perhaps too delicate for the crass world of every day but have a valuable wisdom of their own. They seem fully redeemable by romantic love, which they pursue wholeheartedly and with no fear of future consequences. In fact, the message seems to be that we’re all a bit crazy, and might as well own up to it, for the sake of ourselves and our planet. In the great scheme of things, whether a real-life Joon can build an adult life for herself with Sam’s help is surely debatable. His charm notwithstanding, he’s barely literate, and seems to live in a fantasy realm of his own making. But we’re at the movies, boys and girls,where fantasy outweighs reality every time. This is ultimately a feel-good film that made me feel very good indeed.

A special nod to Rachel Portman’s airy musical score, which helps capture the story’s delicate magic.

No comments:

Post a Comment