The film opens with a sound many people today have never heard. But I remember it well: the clacking of typewriter keys. These keys are being struck, in rapid succession, by two fingers, one on each hand. After 87 years of life and the publication of two best-selling biographies (one in four volumes, with a fifth on its way), Robert Caro has not yet discovered either computerized word processing or touch-typing. Writing in depth about Robert Moses and Lyndon B. Johnson, Caro sticks to the old ways, including carbon-paper copies of all his drafts.

In his long, illustrious career, Caro has always worked with one editor: the now 92-year-old Robert Gottlieb. He is by no means Gottlieb’s only prize author: Gottlieb has overseen the publications of such luminaries as Toni Morrison, Joseph Heller, Doris Lessing, and Bill Clinton. But his relationship with Robert Caro seems to be a special one, though it is not all smiles and pats on the back. As Gottlieb explains it, “He does the book work, I do the clean-up, and we fight.” Partly they fight because Caro, an obsessive researcher who started out as a newspaper man, turns in drafts that are many thousands of words over their contractual limit. That’s why Caro lugs his massive drafts into Gottlieb’s New York office, where together (always with a pair of #2 wooden pencils) they wrestle each book into submission.

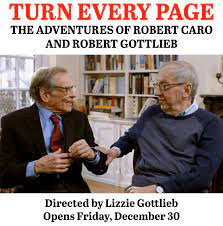

This is what we see on screen in the new documentary, Turn Every Page, It was shot over five years by Gottlieb’s filmmaker daughter, Lizzie Gottlieb. But despite her close proximity to her father and his most famous client, Lizzie did not get total access to their working relationship. Yes, they are separately candid in answering her questions (says Gottlieb admiringly about Caro’s accomplishments, “Anyone can be adorable but not everyone can be industrious—with good results”). But the two men steadfastly refused ever to sit for an on-camera interview together. It was only near the end of the filmmaking process that Lizzie was allowed to film them working—emphatically changing words and x-ing out rejected passages. In those scenes we’ll never know exactly what they were saying, because she was expressly forbidden to record sound.

We do learn, though, a great deal about Caro’s research process. A strong believer in conveying the impact of place on a biographical subject’s life story, Caro long ago persuaded wife Ina to move with him to the impoverished Texas hill country, all the better to soak up the atmosphere in which President Lyndon Johnson was raised. This helped particularly when he conducted a key interview with Johnson’s brother, Sam Houston Johnson. Though he had interviewed Sam Houston several times before about his brother’s childhood, Caro distrusted the results. Aside from a drinking problem, Sam Houston had a reputation as a spinner of tall tales. But following a religious conversion and a period of sobriety, Sam Houston was persuaded by Caro to be interviewed inside the old family home. Caro seated him at the well-worn Johnson dinner table, then stood behind him, frantically taking notes as the man—encouraged, surely, by the once-familiar surroundings—began to reminisce. This, of course, is exactly what Caro was hoping for. I’m only amazed that he trusted to his notetaking (and not a pocket tape recorder) to get it all down.

Caro told Lizzie that all those carbon copies of his drafts were stored in a kitchen cupboard. Near the end of her film, he opens the cupboard door : thousands of sheets of paper are stuffed inside. Who knows what additional treasures they contain?

Postscript: Robert Gottlieb passed away on June 14, 2023, at the age of 92.

No comments:

Post a Comment