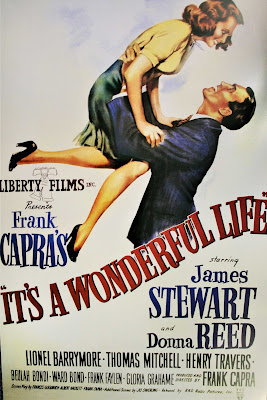

Was the Christmas perennial, It’s a Wonderful Life, covert Marxist propaganda? What about a 1945 tearjerker called Pride of the Marines, regarding a U.S. Marine who loses his eyesight at Guadalcanal? Or a 1948 fantasy-drama called The Boy with Green Hair?

We think of the bad old days—when American politicians were spotting Communists on every corner—as the McCarthy Era. That described the early 1950s, when a certain senator from Wisconsin was accusing most of the U.S. State Department (not to mention the honchos of the Truman administration) of being under the thumb of Soviet Russia. In Hollywood, though, the Red Scare began earlier, just a few years after the end of World War II. When the USSR shifted, in the public’s perception, from being one of the Allies defeating Nazi Germany to a dangerous enemy out to undermine the American system, the movie industry was quick to try removing from its midst anyone who’d once had the slightest admiration for Karl Marx or for Soviet ideology.

L.A.’s Skirball CulturalCenter is currently playing host to a traveling exhibit called Blacklist: The Hollywood Red Scare. The exhibit’s focus is on writers and others who lost their livelihoods (and sometimes their lives) when their patriotism was questioned by studio bosses. In that era, it became verboten to belong (or to have belonged, even decades earlier) to the American Communist party. And guilt by association was the rule, not the exception. Woe to the Hollywood figure called before a Senate committee to answer the question, “Are you now or have you ever been a member of the Communist Party?” (You were expected to get yourself off the hook by ratting out your friends.) An unverified mention in a publication called Red Channels could destroy your career, though a quiet pay-off to the editor could help your problem vanish.

Jews, Blacks, and members of other minority groups were, in that era, particularly suspect. Philip Loeb, who played Gertrude Berg’s husband on a popular radio broadcast called The Goldbergs, was accused of Communist sympathies in Red Channels. Though he denied the accusation, it led to his firing and then to his suicide. Popular leading man John Garfield, whose wife had once been a Party member, was hounded into an early death. Some major Hollywood stars, led by Lauren Bacall and spouse Humphrey Bogart, rallied to form a Committee for the First Amendment in support of their fellow actors, but studio bosses quickly scared them off.

Perhaps hardest hit were Hollywood’s veteran screenwriters, who found themselves living overseas and writing under fake names, only collecting the Oscars they’d earned (like Dalton Trumbo’s for Roman Holiday) decades later. For me the most eye-opening part of the exhibit was the display of FBI commentary casting suspicion on the era’s most popular films. It’s a Wonderful Life? It was suspect because it contained ““a rather obvious attempt to discredit bankers.” The Best Years of Our Lives? This poignant 1946 drama of 3 servicemen trying to re-adjust to civilian life, winner of 9 Oscars including Best Picture, was regarded with disfavor for portraying the upper class unattractively. Because Gentleman’s Agreement, a Best Picture winner that boldly confronted anti-Semitism, included in its cast of characters a bigoted cop, it was accused by the FBI of being “a deliberate attempt to discredit law enforcement.” Body and Soul? “It portrays the rich and successful man in a bad light and the finest character of them all is a colored fighter.”

And The Boy With Green Hair? Who says that looking different is a GOOD thing?

No comments:

Post a Comment