I didn’t know much about Otto Friedrich when a fellow member of the Biographers International Organization suggested I read Friedrich’s classic history of Hollywood. Called City of Nets (with a nod to Bertolt Brecht’s crass, venal City of Mahagonny), it focuses on the 1940s, a turbulent era in moviedom. Devoting each chapter to a year in that decade, Friedrich takes the reader from a society at war to a society not quite sure on how it wants to celebrate and preserve the peace.

A journalist and historian interested in the evolution of culture, Friedrich tackles Hollywood as a place that fulfills the world’s dreams while also dangling celebrity and fortune in front of the lucky few who’ve figured out how to play the game. He spends many pages on Hollywood at war: the famous actors marching off to do battle (or getting cushy commission to make propaganda films); the glamorous actresses hustling war bonds and serving up doughnuts at the Hollywood Canteen. Regarding the post-war years, Friedrich chronicles in detail the rise of political hysteria leading up to the blacklisting of Hollywood writers with Communist sympathies, as carried out by studio heads fearful of governmental censure. His account looks closely at those on both sides, laying bare the inept strategies used by the so-called Hollywood Ten when called before a Congressional committee. Alas, their ill-considered testimony probably lost them key supporters throughout the industry and the public sphere as well.

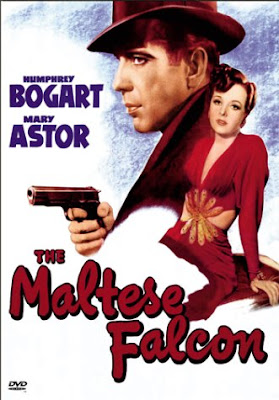

But I was most fascinated by the evolution of Hollywood stars in this era. The book was recommended to me initially after I wrote about early films (like Dead End) in which Humphrey Bogart was typecast as a powerful bad guy, someone who lacked any redeeming qualities whatsoever. The transformation came when fledgling director John Huston was looking for a leading man to play Sam Spade, a tough but principled private eye, in the umpteenth screen adaptation of Dashiell Hammett’s The Maltese Falcon. The role had been turned down by virtually every tough guy on the Warner Bros. payroll: George Raft, Paul Muni, Edward G. Robinson, John Garfield. But Bogart leaped at the chance to play his first starring role. It made him an icon, and an actor whose stoic charisma the rest of young Hollywood couldn’t help but admire. Suddenly a new sort of antihero was born.

Friedrich presents equally interesting tales of two new Hollywood glamour girls. When Betty Perske, a sleek eighteen-year-old model, was spotted by Howard Hawks on the cover of Harper’s Bazaar, he thought she might be just the dame to cast opposite Bogart in To Have and Have Not. She was shy and had a high-pitched voice, but she was nothing if not eager to be educated. Under Hawks’ tutelage, she lowered her voice and became Lauren Bacall. Because Hawks felt women were most exciting when they played hard to get, she unveiled an on-screen arrogance that became her persona from then on. It didn’t hurt her career, of course, that she and Bogart quickly fell deeply in love.

An even more dramatic metamorphosis turned Margarita Carmen Dolores Cansino into screen goddess Rita Hayworth. A young New Yorker whose father had toured as a Spanish dancer, she turned out to be infinitely malleable. Her dancing was her strong suit; the studio dyed her long bob of hair a flaming red, dubbed in someone else’s singing voice, and cast her as the naughty (or is she?) Gilda. Alas, she said years later, “Every man I’ve known has fallen in love with Gilda—and wakened with me.”

No comments:

Post a Comment