The death of Norman Lear—writer, producer, social crusader—has set us all to thinking about the ways that mass media can influence public opinion. Lear’s creation in 1971 of a lovable bigot, Archie Bunker on TV’s All in the Family, launched household conversations that are still going on. It was the start of the era in which the so-called “boob tube” was used for something other than benign entertainment, in which the tough issues of the day were explored, in a humorous but pointed context.

After nine seasons of All in the Family, Lear created many other TV series, most of them exploring how people of different backgrounds come together, and are pulled apart. Not content to weave his own views about tolerance and progressive politics into teleplays, Lear in 1980 introduced People for the American Way, an important advocacy group meant to combat the right-wing views of the so-called Moral Majority. He was hardly one to keep silent in the face of injustice.

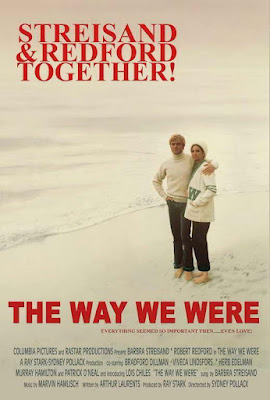

I have no idea what Norman Lear thought of Sydney Pollack’s 1973 film, The Way We Were. This bittersweet romance between a politically left-wing Jewish gal (Barbra Streisand) and a hunky college athlete with writing skills and WASP self-importance (Robert Redford) was beloved by many for its mating of two top stars of the era as well as for a title ballad that has never gone out of style. The Way We Were, adapted by playwright Arthur Laurents from his own novel, was nominated for six major Oscars, winning for both its song and its musical score. It also made major waves at the box office. I suspect Lear might have responded to the film’s central idea of opposites attracting, but would have liked it better if Pollack hadn’t been forced by his studio to cut heavily the section dealing with McCarthyism and the Hollywood blacklist.

As for me, seeing The Way We Were again after so many years, I find I am not a fan. Still, though I have always resisted the charms of Barbra Streisand, I can’t help but praise her for a funny and heartfelt performance. Her Katie Morosky is someone worth paying attention to, both when she’s weak and when she’s strong. On the other hand, I have no great love for Robert Redford’s performance as the feckless Hubbell Gardiner. We’re supposed to believe he’s a sensitive and immensely gifted writer, one who can achieve the upper echelons of his craft based on his skill alone. But all I saw on screen was a blandly handsome guy with a Malibu beach house and a poor taste in friends. He seems shallow, and Katie’s long-term infatuation with him makes her a bit shallow as well. With all her smarts, it’s a shame she can’t make a better choice of soulmates. And the political/social context that is supposed to add to the film’s meaning is skipped over so lightly that it might as well not be there at all.

My colleague Julia L. Mickenberg, who specializes in women’s history at the University of Texas at Austin, has a unique perspective on this film. Her recent online piece for Ms. relates to the once-celebrated Jewish author and activist Eve Merriam, about whom she is currently writing a biography. Merriam, it seems, was a close college friend of Arthur Laurents, and served as his model for the Katie Morosky character (created by Laurents with Streisand in mind). She was also an important public figure in her own right. A big thank-you to Julia for adding to my understanding of a forgotten but fascinating figure.

No comments:

Post a Comment