When I was a young married, there arose (just a stone’s throw from 20th Century Fox Studios) something called Kentucky Fried Theatre. The invention of three antic young men from the University of Wisconsin-Madison, the theatre housed a popular sketch comedy show called My Nose. This oddball title allowed the trio to place ads in the Los Angeles Times announcing, “My Nose Runs Continually.” An ambitious fellow named Lorne Michaels once showed up in the audience with an NBC honcho, Dick Ebersol, whom he was trying to interest in the prospect of a network comedy series. Ebersol was convinced, and the result was (ta da!) Saturday Night Live.

Meanwhile the three Kentucky

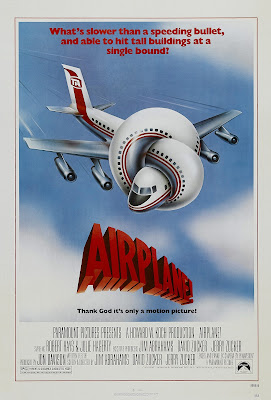

Fried Theatre cut-ups moved from the live stage into movies. They soon struck

comic gold with their 1980 release, Airplane! By this point, Jim

Abrahams and brothers David and Jerry Zucker were no longer starring in their

own material (playing onstage such goofy roles as a strip-teasing Mister Rogers,

who removes his jacket and shoes but doesn’t stop there). Instead the artistic

ménage à trois was responsible for both writing and directing a $3.5 million movie

that took in a reported $171 million worldwide, and was inducted into the

National Film Registry in 2010 for its cultural and aesthetic significance.

These three madcap writer/directors have just come out with a behind-the-scenes memoir, “Surely You Can’t Be Serious”: The True Story of Airplane. It was my pleasure to hear David Zucker speak in person about how the film came to be. This was the era of all-star disaster movies like Airport (a crisis in the air!), The Poseidon Adventure (a crisis at sea!), and The Towering Inferno (a crisis in a big building!) Arthur Hailey, whose novel begat the film Airport had earlier contributed to the screenplay of a 1957 thriller called Zero Hour! Its hero is a disgraced World War II flyer who—while a passenger on a long-distance flight—must unexpectedly take over the cockpit of a large jetliner when passengers and crew are felled by food poisoning. Sound familiar? Yes, this basic plot shows up in extremis in Airplane!, with the addition of some outrageous sight gags, some deliberately corny jokes, and a blow-up autopilot named Otto.

When Zucker and company went to cast their movie, they took the matter seriously in all senses. They had no desire to follow in the footsteps of funnyman Mel Brooks, who stocked his casts with outsized performers like Dom DeLuise. Instead they looked for the sorts of straight-arrow actors who would have starred in serious B-movie action dramas like Zero Hour! That film had featured Dana Andrews and Sterling Hayden. In Airplane! Zucker Abrahams Zucker (informally known as ZAZ) showcased the work of Leslie Nielsen, Peter Graves, and Robert Stack, none of whom had a reputation for zany comedy. For their leading lady, the stewardess whose heart Robert Hays is trying to win back, they found Julie Hagerty. It was her very first movie role, and her wide-eyed innocence fit in nicely with the insanity going on all around her. (Zucker discloses that another candidate for the role was Sigourney Weaver, who came to her audition in full 1940s stewardess garb, and then started making demands for script changes.)

Why was basketball star Kareem Abdul-Jabbar cast as First Officer Roger Murdock? Because this was an era when sports stars were being shoe-horned into cameo roles in major movies. Zero Hour! in fact used as one of its pilots a famous retired footballer, Elroy “Crazylegs” Hirsch. Surely Kareem wore his wings well. But don’t call him Shirley.