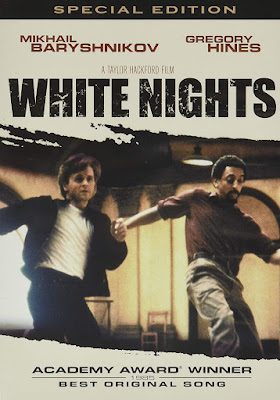

Given Vladimir Putin’s unprovoked invasion of Ukraine, I’m not feeling too kindly toward Mother Russia. That’s why I chose to watch White Nights, a Russia-set thriller from 1985, six years before the fall of the Soviet Union. Its title, often associated with a story by Dostoevsky, refers to the few days in summer (at least in northern hemisphere countries near the Arctic Circle) when the sun never sets. That’s the eerie period in which the climax of this movie takes place. But its main attraction is an unusual cast, featuring dance greats Mikhail Baryshnikov and Gregory Hines, along with Helen Mirren and Geraldine Page. In a highly sympathetic key role, Isabella Rossellini made her international film debut, playing a Russian interpreter who has become Hines’ wife.

Today Baryshnikov is, at 74, no longer the svelte young dancer who once set the ballet world ablaze. A treasured member of the Leningrad-based Kirov troupe, he made international headlines by defecting to Canada in 1974, as a way of broadening his artistic horizons. Since living in the west, he has danced in principal roles with American Ballet Theatre, and for nine years was the company’s artistic director. He has also been deeply involved with modern dance, notably with choreographer Twyla Tharpe, whose imprint is strongly felt on White Nights. His first film acting role came in 1977 with The Turning Point, for which he won an Oscar nomination. Much more recently he was featured as a love interest in the last season of Sex and the City.

The biography of Gregory Hines (1946-2003) is less dramatic, but no less impressive. One of the most celebrated tap dancers of all times, Hines also excelled at acting and singing, skills that are featured in White Nights. As an African-American, he doubtless lost out on many career opportunities, but he’s remembered for roles in films like The Cotton Club and Running Scared. His ethnicity plays a major part in White Nights, in which he stars as a Black entertainer who (somewhat like Paul Robeson before him) makes his home in the USSR as a political protest against the nation of his birth. Alas, he finds himself stuck in Siberia, entertaining tiny groups of locals with selections from Porgy and Bess.

Baryshnikov plays Kolya, who—having defected from Russia and the Kirov—quickly becomes a global dance celebrity. En route from New York to Tokyo, his plane makes an emergency landing at a Siberian air base, and the KGB is delighted to have the famous man back on Russian soil. The icy Colonel Chaiko makes him a sweet deal: if he resumes his Kirov career, he gets unimaginable perks. If he refuses, prison awaits. Hines’ Ray Greenwood enters the picture as a minder, assigned to keep an eye on the ballet superstar. Of course the two men, initially at odds, gradually bond over dance and much else.

What makes the film memorable is the amount of spontaneous-looking dance it contains. Both Kolya and Ray reveal their emotions most strongly through dance moves. At the very heart of White Nights is a spectacularly jazzy routine in which the two very different but very talented men find themselves on common ground. But of course a film on this subject needs an action climax, and this one packs a wallop, calling on Baryshnikov’s physicality as well as Rossellini and Hines’ soulful connection. Helen Mirren shines as Kolya’s Russian former partner in dance and romance. And though our glimpses of Leningrad (aka St. Petersburg) are lovely, life in Russia doesn’t seem like something you’d want to experience anytime soon.

No comments:

Post a Comment