I’ve been on a Billy Wilder kick lately, sparked by reading Joseph McBride’s mammoth 2021 appreciation, Billy Wilder: Dancing on the Edge. McBride, yet another Roger Corman alumnus who’s made good, has been in the course of his long career a screenwriter, a journalist, a critic, and a professor of film. As a biographer of great movie directors he’s endlessly prolific, with a book on the Coen Brothers newly available this month.

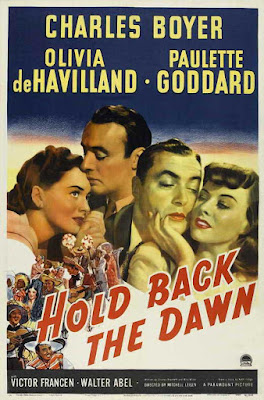

Joe’s writing has whetted my appetite for the more overlooked films in the Wilder canon. Of course I’ve seen such classics as Sunset Boulevard and Some Like It Hot. One Wilder movie not remembered much today is 1941’s Hold Back the Dawn, on which he served as a screenwriter, along with writing partner Charles Brackett, for journeyman director Mitchell Leisen. The well-received film was nominated for six Oscars, including Best Picture, Best Adapted Screenplay, and Best Actress. (Leading lady Olivia de Havilland lost out to her sister, and arch-rival, Joan Fontaine, who won for Hitchcock’s Suspicion.) But neither Brackett nor Wilder looked back on this project fondly.

Joe McBride agrees with me that Hold Back the Dawn was partly harmed by a title that seems to promise the wrong things. Before watching the film I jumped to the conclusion that it was an action thriller, maybe a World War II drama with partisans bravely staving off the enemy. It’s definitely war-related, but this is hardly an action film. Instead, it’s a sensitive tale of desperate European immigrants, at the height of the Nazi era, stuck in Mexico while they try to find a way across the border. What makes it particularly fascinating for Joe and for me is that it mirrors in several key ways Wilder’s own story. The leading character in Hold Back the Dawn, played by Charles Boyer, is a Romanian in a Tijuana-like border town, trying to reach the U.S. Back home he was a dancer and, it’s strongly implied, a gigolo. When he comes across his former dance partner, now visiting Mexico as a tourist, she persuades him that the way to gain access to the U.S. is to marry some innocent American dupe, keeping up the deception just long enough to gain legal status. And so he quickly woos and wins de Havilland, a naïve schoolteacher from Azusa, California, who’s south of the border with a broken-down van and a gaggle of noisy schoolkids. Sweetly, though improbably, it turns into a love story.

Wilder would doubtless deny ever being a gigolo, but as a struggling journalist in Berlin he had worked in swanky cafes as an eintänzer (or dancer for hire), charming the ladies who lunched. And he had his own moment of immigrant desperation in Mexico, urgently persuading a member of the American consulate staff to let him cross the border and make his way to Hollywood. McBride posits that Wilder’s take on life was permanently stamped by the era in which he fled Nazi Germany, where his Jewish roots were about to deprive him of a flourishing film career. He quickly found success in movieland, but was never able to rescue his mother and other family members ultimately lost to the Holocaust. Such life experiences naturally helped shape an acerbic outlook that many have called cynical, at the same time that his films reveal a subtle romantic streak. It was Leisen’s cutting of a scripted moment in Hold Back the Dawn—the so-called “cockroach scene” in which Boyer’s character expresses his own despair—that convinced Wilder to direct his own material in future. The rest is movie history.

Fantastic piece. Learned SO much and it all was presented in such a warm voice.

ReplyDeleteThanks, as always!

ReplyDelete