We seem to be part of a Nora Ephron revival. Amazon, bless ‘em, keeps reminding me to purchase Nora Ephron: The Last Interview: And Other Conversations. And June 7 was the publication date for a new biography by Kristin Marguerite Doidge, simply titled Nora Ephron: A Biography.

Doidge’s lively book is an apt tribute to a screenwriter, director, novelist, essayist, and all-around bon vivant who looked at the world wryly, but never let romance go out of her life. Though Ephron left us in 2012, after a rare blood disorder with an unpronounceable name turned into leukemia, her ebullience and can-do spirit continue to inspire. Boy, do we need her now!

Nora was the oldest daughter in a family of writers. Her parents, Henry and Phoebe Ephron, collaborated on a hit Broadway comedy, Take Her, She’s Mine, about a father learning to let go of his blossoming young daughter. It wasn’t exactly autobiographical, but as the eldest of four daughters in the Ephron household, Nora could see some of her own Wellesley experiences playing out on stage (after all, they did use direct quotes from her letters home!). The Ephrons also enjoyed a long Hollywood screenwriting career, culminating in an Oscar nomination for Captain Newman, M.D. But their artistic success didn’t make for a happy marriage, given that it was fueled by alcoholism and infidelity. Though Phoebe famously told her brood to mine their private lives for artistic material – “Everything is copy”—she was secretive about her own deep unhappiness.

Nora, for her part, grew up determined to make her own way as a writer. Maybe it was the fact that she was named after the heroine of Ibsen’s A Doll’s House, the one who climactically slammed the door on a life of domestic subservience, but she never stopped fighting for what she wanted. Starting out as a journalist, she eventually won the battle to be accepted in an industry that had long avoided hiring women. In 1976, she married Carl Bernstein of Watergate fame, but the union fell apart when (about to give birth to her second child) she discovered his long-term affair with the daughter of a British prime minister. Eventually she recovered enough from this shock to write a close-to-the-bone but hilariously funny novel, Heartburn, then adapted it for the 1986 film directed by Mike Nichols.

By that point, she had

already transitioned to Hollywood, writing a powerful true-to-life screenplay

for Silkwood with her

friend and fellow journalist Alice Arlen. That 1983 drama about the gutsy whistle-blower at a nuclear plant

earned five Oscar nominations, including one for Ephron and Arlen. The director was Mike

Nichols, who became one of her many close friends, as well as a mentor for her

moviemaking dreams. Mike’s guidance as

well as her own courage and passion for detail led her into directing her own work. Calling upon the comedic

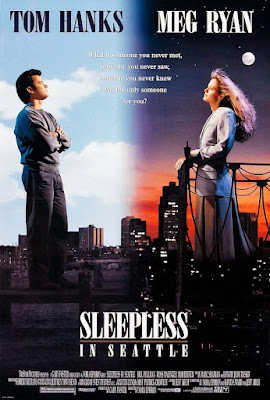

flair she’d shown in everybody’s favorite romcom, 1989’s When Harry Met Sally . . . (helmed by Rob Reiner), she directed

such hits as Sleepless in Seattle and

You’ve Got Mail. Not everything was a

winner—the screwball antics surrounding a Venice, CA crisis hotline on

Christmas Eve in Mixed Nuts don’t

really land—but her string of box office and critical successes would make

anyone proud. Meanwhile, she wrote Off-Broadway and Broadway plays and had

several bestselling collections of essays, including I Feel

Bad About My Neck: And OtherThoughts On Being a Woman.

Her last film, 2009’s Julie & Julia, called upon her passion for cooking and for eating. As a person who couldn’t order in a restaurant without requesting elaborate changes to the standard fare, Nora Ephron knew exactly what she wanted. Too bad she isn’t still among us. As for me, I’ll have what she’s having.

Attention, Angelenos: Kristin Marguerite Doidge will

be appearing at 7 p.m. g on Tuesday, June 14 at Book Soup (8818 Sunset Blvd.,) to discuss Nora

Ephron: A Biography. I’ll be on hand to conduct a Q&A with Kristin. Y’all

come!

Hiya. So, Nora, like the fictional Sally, couldn’t place a restaurant order without saying, “and put the dressing on the side”? Cool. Enjoy the Q & A on the 14th. My wife’s enjoying Delia’s “Left on Tenth,” her autobiography. AMLevinson.

ReplyDeleteNora didn't only want the dressing on the side. She'd insist on toasted bread, extra-crisp bacon, and a spread other than mayo on the sandwich.

ReplyDelete