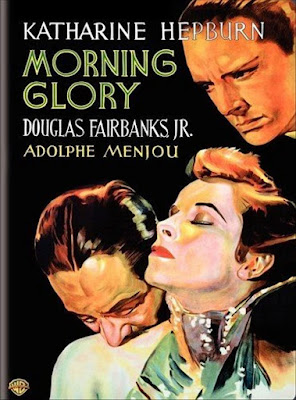

Having recently watched Brad Pitt in the part (in A River Runs Through It) that shot him to fame and fortune, I’ve now found myself marveling at the star-making role of another Hollywood legend. You know her name: Katharine Hepburn. In a nifty compilation of five Oscar-winning DVDS that span the 1930s through the 1950s, I discovered Morning Glory, a behind-the-footlights hit from 1933. Based on a then-unproduced play about an eager young would-be stage actress, it’s not a terribly good motion picture. Hepburn, though, is unforgettable. No wonder the role of Eva Lovelace won her the first of her four Oscars for Best Actress. (Back in that era, there were only three nominees in her category, but still . . !)

Eva, who started out in a rural Vermont town as Ada Love, is now—after some success in a local theatre troupe—trolling for stage roles in New York City. Convinced of her own talent, she tells anyone who will listen about her plans for future stardom. (Marriage is out, because she intends to be embroiled in various magnificent scandals. And, though she longs to take on the great dramatic roles, she’ll refuse any part for which she doesn’t feel a strong personal connection.) In the office of a legendary Broadway producer, played with panache by Adolphe Menjou, she alternates between brashness and a fawning eagerness to please. When he asks her name, she quickly answers, “Eva Lovelace. Like it? I can change it if you don’t.”

The centerpiece of the film is a drunk scene that occurs after Eva’s elderly British admirer, a legendary character actor played by legendary character actor C. Aubrey Smith, takes her to a first-night party at Menjou’s lavish flat, where she mingles with a roomful of elegant society folk. Plainly dressed and emaciated from living on a meager diet, she quickly gets tipsy on two glasses of champagne, after which she trumpets her own genius to anyone within earshot. Suddenly she launches, without fanfare, into Hamlet’s “To be or not to be” soliloquy, followed by a lovely rendering of Juliet in the famous balcony scene. As onlookers titter, she turns downright kittenish toward Menjou: for me seeing the often imperious Hepburn in the throes of girlish infatuation was an unexpected treat.

Morning Glory is a so-called pre-code movie, one made before the infamous Hayes Code of the mid-1930s mandated issues of on-screen morality. But the film’s one instance of outré behavior is so subtle that I nearly missed it altogether. At that eventful first-night party, after finishing her Shakespearean recitation, Eva collapses and is trundled off to the guest room by a butler. Come morning, dialogue hints that Menjou’s character has had his way with a woozy but willing Eva. Feeling guilty (which is certainly to his credit), he cuts off all future contact.

But—wouldn’t you know it?—she finds her pre-destined stardom all the same. Not to mention the love of a talented young playwright, a thankless role for Douglas Fairbanks Jr. The twist is that she’s suddenly unready for this brilliant turn of affairs. In a poignant interchange with a sympathetic wardrobe mistress, she worries about ultimately being a morning glory. (The cautionary title refers to once-bright stage stars who all too quickly fade from view.) Perhaps romantic love and not fame should be enough for her? The ending remains ambiguous, but I sensed that Eva remains Katharine Hepburn to the core. Surmounting her fears, she insists she wants it all.

Historical footnote A updated version of Morning Glory, redubbed Stage Struck, was released in 1958, starring Henry Fonda and Susan Strasberg. Who knew?

No comments:

Post a Comment