In 1964, the cool kids discovered Greece. Greek line-dancing was taught to enthusiastic hipsters at folkdance cafés across the country. Souvlaki was the snack of choice, and ouzo became a favored tipple. Everyone (even Joni Mitchell) wanted to go camp out on a lonely beach on some Greek isle. Why this passion for all things Hellenic? Chalk it up to the outsized success of a small film, Zorba the Greek.

Zorba The Greek was directed by Michael Cacoyannis, a talented Cypriot who launched his career with works performed in Greek. In 1962 I first encountered his Electra, adapted from the classical text of Euripides, and I still remember its raw power. Years later I marveled at how he could people The Trojan Women with some of the world’s brightest international stars (Katharine Hepburn, Vanessa Redgrave, Genevieve Bujold, Irene Papas as Helen of Troy), set them against the rugged Greek landscape, and vividly convey what Euripides’ anti-war tragedy was all about.

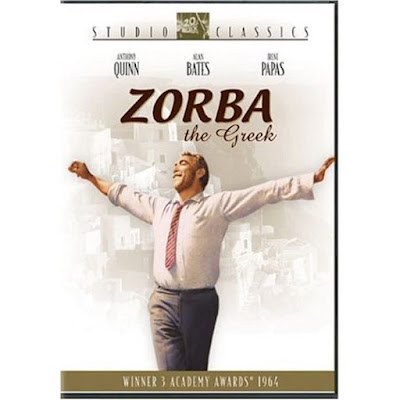

I was an arty kid, willing to read subtitles and open to watching the playing out of a text that dates back to 415 BC. Admittedly, not everyone in my generation had my arcane tastes. But we all found it easy to adore Zorba the Greek, a film full of love and laughter, at the same time that it explored in heart-wrenching detail the tragedies of life. Adapted by Cacoyannis from a well-loved novel by Nikos Kazantzakis, a nine-time nominee for the Nobel Prize for literature, the film gave Hollywood’s Anthony Quinn (who also produced) his most iconic role. He’s a marvel as a man who functions as a life-force: passionate, roguish, someone who fights off tears by dancing his heart out on the sands of Crete.

Quinn’s opposite number in the film is Alan Bates as Basil, the strait-laced young Englishman who must be taught to laugh at fate. Then there’s Lila Kedrova, who picked up an Oscar for her portrayal of a vulnerable Frenchwoman, the keeper of a shabby hotel in a small Greek village, The final main character, played by Cacoyannis favorite Irene Papas, is known only as The Widow. Her essentially non-speaking role calls forth all her beauty and dignity. She’s the solitary young woman, clad in black from head to toe, who moves silently through the town, hated by all the local wives, lusted after by their husbands. It’s clear enough to all of us that something dreadful is about to happen.

As viewers, we never find out anything about the Widow, nor what became of her husband. In a sense, we in the audience are in the same position as Alan Bates’ character: we’re outsiders, learning about a culture we don’t entirely understand. Though the movie contains some brief conversations in subtitled Greek, mostly it’s in English, spoken by characters (like Basil, like Kedrova’s Madame Hortense, even like Zorba himself) who are not genuinely part of the local scene. In a film that acknowledges a language barrier as one of the things that separate people from one another, visuals are particularly important. And so they are here. The Oscar-winning black & white camerawork of Walter Lassally graphically highlights the stark drama that’s part of this town’s life. One moment I particularly recall captures the moments immediately following the death of Madame Hortense. The elderly crones of the neighborhood, all clad in widow’s weeds, steal into the bedchamber where her illness-wracked body still lies. Like the harpies in classical tales, they silently make off with every trinket she owns, leaving her room stripped bare..

Then of course there’s Mikis Thedorakis’ evocative, dance-worthy score. Opa!

No comments:

Post a Comment