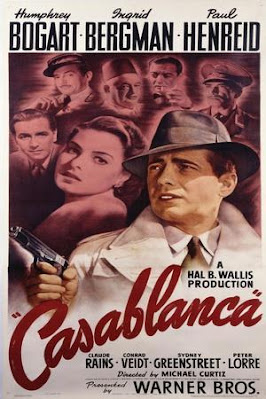

Recently I was on a transatlantic flight: destination Morocco. The plane landed at Mohammed V Airport in Casablanca, the country’s largest and most international city. One of many choices on my plane’s seatback television screen was that golden oldie from 1942, Casablanca. It’s still revered, more than 80 years later, as one of the great screen romances of all time. The movie’s ability to combine a poignant love story with a World War II thriller is part of why it’s lasted so long. Among its many honors, it was in the first class of films accepted (in 1989) into the National Film Registry due to its cultural, historical, and aesthetic significance.

The release history of Casablanca is a fascinating one. The film’s setting in a North African city that was then part of a French protectorate but also served as a gateway to far corners of the globe ensured there’d be plenty of on-screen friction between a multitude of nationalities. Casablanca was released at the height of World War II, so of course the worst of the bad guys who frequent Rick’s Café are Nazi officers. They’re linked with functionaries of the French Vichy government who perform their duties under the heavy German thumb. That’s why in March 1943 the film was officially banned in Ireland, which sought to retain its wartime neutrality. Two years later, Casablanca was finally released in Ireland, after trims were made to romantic dialogue focusing on Rick and Ilsa’s Paris love affair.

Of course German audiences would not see Casablanca until long after the war was over. A shortened and heavily edited version was released by Warner Bros. in West Germany in 1952. Remarkably, this de-Nazified Casablanca changed Ilsa’s husband, Victor Lazlo, from a heroic Czech Resistance fighter who has escaped from a Nazi concentration camp to a Norwegian atomic physicist who has broken out of jail. It was not until 1976 that German audiences could watch the film in its original version.

Lovers of Casablanca always point to the dramatic intensity of the film’s supporting players, especially in the famous “duel of the anthems” sequence. Nazi soldiers kicking back at Rick’s Café enthusiastically begin to sing “Die Wacht am Rhein,” but their voices are drowned out by the rest of the crowd’s heartfelt rendition of the Free French anthem, “La Marseillaise.” The closeups in this section are dramatic, partly because so many of the players—notably Madeleine LeBeau, Marcel Dalio, Peter Lorre, and Conrad Veidt—were themselves exiles and refugees. (Ironically, Jewish actors who had fled Europe during Hitler’s reign often found their careers depended upon playing Nazi roles in Hollywood.)

The screenplay for Casablanca, based on an unproduced play, was the work of many hands, notably those of brothers Julius and Philip Epstein. The story goes that the Epsteins and others were busy writing even while the film was being shot. That’s why Ingrid Bergman, as Ilsa, honestly wasn’t clear on whether she’d be getting on a plane with her husband (Paul Henreid) or staying behind with onetime love Humphrey Bogart. She’s said to have faulted her own performance because she wasn’t sure as an actress which option her character would choose. But generations of moviegoers agree that her uncertainty was exactly right for this film.

Casablanca was rushed onto movie screens to tie in with the real-life North African offensive that put the locale on the international map. How well does the film reflect the actual city? Not at all, because it was filmed on a Hollywood backlot. There’s a Rick’s Café in today’s Casablanca, but it’s strictly a tourist trap.

Much has been written

about the making of this film. I’ve used other sources, but want to cite here

Noah Isenberg’s 2017 publication, We'll Always

Have Casablanca: The Life, Legend, and Afterlife of Hollywood's Most Beloved

Movie