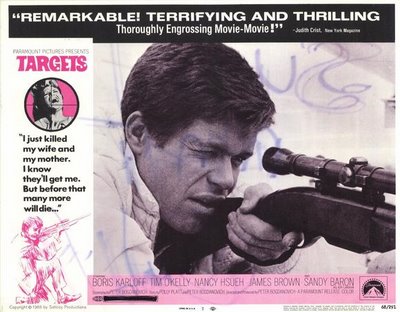

Critic Jason Zinoman recently spoke to Terry Gross of Fresh Air about his new book, Shock Value: How a Few Eccentric Outsiders Gave Us Nightmares, Conquered Hollywood, and Invented Modern Horror. The interview kicked off with discussion of a low-budget 1968 film that helped launch the modern horror genre. This was Targets, which unforgettably pairs the aging Boris Karloff with a sniper holed up at a drive-in movie theatre. Zinoman praised Targets as a Peter Bogdanovich film: Bogdanovich not only wrote and directed, but also plays a version of himself, a young filmmaker trying to persuade horror star Byron Orlock (Karloff) to appear in one last movie. As the producer who had stipulated that Karloff footage from The Terror must be incorporated into the new film, Roger Corman got mentioned too.

But no one said a word about Polly Platt. In 1968, Platt was Bogdanovich’s wife and artistic partner. Though content to stay in the background as Bogdanovich’s star rose, she contributed hugely to Targets, as well as to films before and since. I’ve just learned that Polly, whom I interviewed at length in 2008, has succumbed to the ravages of Lou Gehrig’s disease. It seems time to set the record straight.

Polly Platt and Peter Bogdanovich were young marrieds, passionate about film, when they met Roger Corman in 1961, following a screening of Last Year at Marienbad. As Polly described it to me, “Roger wanted to make money and we wanted to make movies. It was a perfect marriage.” By 1964, the pair were polishing Chuck Griffith’s ungainly script for Corman’s The Wild Angels. While Bogdanovich, as Corman’s all-purpose production assistant, did chores on the Wild Angels set and ended up directing second unit, Platt designed the costumes and served as stunt double for female lead Nancy Sinatra. She also played supportive spouse. A friend from those days remembers Bogdanovich’s near-total dependence on her: “Polly, what do I want for breakfast?”

On Corman’s Voyage to the Planet of Prehistoric Women, a Russian-made sci-fi film with added footage featuring Mamie Van Doren as a mermaid, Peter directed the new material under a pseudonym, while Polly was the very novice production coordinator. Then came Targets. The germ of the story was Polly’s realization that for Baby Boomers true horror was represented by President Kennedy’s sudden death.. She told me, “I had this terrible fear that some day I would open the front door of our house on Saticoy Street and somebody would just shoot me for no reason. Or that someone would drive by with a rifle and shoot Peter in bed, “ By then the mother of a young daughter, she carved out time to contribute to Targets’ script as well as its production design.

In 1971, she had an equally hands-on role in Bogdanovich’s break-through film, The Last Picture Show. But she suffered tremendous emotional pain when, during production, he left her for the film’s ingénue, Cybill Shepherd. A true survivor, Polly went on to a successful mainstream career as a costume designer, Oscar-nominated production designer, and producer of such hits as Broadcast News and Say Anything. . . . One of her final projects was Corman's World: Exploits of a Hollywood Rebel. She graciously served as executive producer for this film tribute to the mentor who made it all happen, for better and for worse.